|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

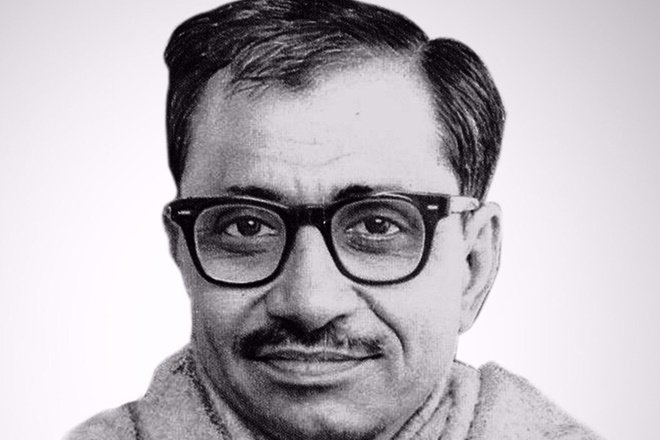

Deen Dayal Upadhyaya was the second top Jana Sangh leader to die under mysterious circumstances — the first being the founder, Syama Prasad Mookerjee, who also died mysteriously on June 23, 1953. Mookerjee too was 52 at the time of his demise.

Syama Prasad Mookerjee walked out of Jawaharlal Nehru’s cabinet due to ideological differences and started the Bharatiya Jana Sangh (BJS) in 1950. When he approached the RSS for support, the leadership decided to second some of its best pracharaks, including Deen Dayal Upadhyaya, Atal Bihari Vajpayee, Lal Krishna Advani, Sundar Singh Bhandari and Nanaji Deshmukh. Upadhyaya, who would have turned 103 today, became the general secretary of the BJS in the party’s very first session in December 1951 and worked in that capacity for 16 years.

The emergence of BJS was a historic development. The BJS was not just another political outfit but a party with a distinct philosophy and programme. The Congress was the dominant party at that time. The Hindu Maha Sabha, Ram Rajya Parishad and Swatantra Party were no match to the ruling establishment. The communists and socialists too lacked a national appeal and charismatic leadership. The BJS was established to offer a quintessentially Indian alternative to the Nehru’s politics and political philosophy.

For Upadhyaya, politics wasn’t just for capturing power. He would insist on practising value-based and principled politics. The central thrust of his politics was national interest. He was, in fact, a reluctant politician. His mentor, M S Golwalkar of the RSS, once said: “Deen Dayalji was the most reluctant politician, and had many times expressed his distress at the kind of work he has been entrusted with. He would rather prefer to go back to his previous work as a sangh pracharak. I told him that I could see nobody else who would do the work as well as he could. It needed an unshakable faith and complete dedication for a man to remain in this mess and yet be untouched by it.”

That parties could so easily and uninhibitedly form alliances without any commitment to principles and programmes came as a rude awakening to Upadhyaya. The changing contours of India’s political landscape were unacceptable to this idealist. He once said: “Different parties have different viewpoints. People don’t take them into account. Out of goodwill they sometimes feel that certain political parties should get together. But there are certain fundamental issues that justify separate existence of the parties. Goodwill alone is not enough.

That is why we have decided that we won’t live in any imaginary world and enter into an alliance whose success is doubtful. It would be good to work together on issues where a consensus is possible; otherwise we should operate from our respective platforms.”

The general elections in 1967 saw the Congress decline in a number of states. Upadhyaya was forced to abandon idealism for pragmatism and realpolitik as the possibility of forming non-Congress coalition governments emerged in many states. The Samyukt Vidhayak Dal (SVD) experiment — a non-Congress alliance of 15 parties — provided an opportunity for the BJS to become a part of the ruling establishment in several states. But it also raised the hackles of many party workers who saw the arrangement as a compromise with party ideology and beliefs. “Let not the Jana Sangh delude itself that by cohabiting with communists, we will be able to change them. Kharbooja chakkoo par gire, ya chakkoo kharbooja par; katega to kharbooja hi — whether the melon falls on the knife or the knife falls on the melon, it is the melon that gets cut,” argued a party leader.

Upadhyaya had to use a combination of wisdom and realpolitik to convince the cadres about the efficacy of the SVD experiment. “It is an irony of the country’s political situation that while untouchability in the social field is considered to be evil, it is sometimes extolled as a virtue in the political field. If a party does not wish to practise untouchability towards its rival in the political establishment, it is supposed to be doing something wrong. We, in the Jana Sangh, certainly do not agree with the communist strategy, tactics and political culture. But that does not justify an attitude of untouchability towards them. If they are willing to work with us on the basis of issues, or as part of a government committed to an agreed programme, I see nothing wrong in it. The SVD governments are a step towards ending political untouchability. The spirit of accommodation shown by all parties, despite their sharp differences, is a good omen for democracy,” he argued.

Upadhyay became president of the BJS at the party conclave in Kozhikode in December 1967. In the RSS scheme of things, pracharaks are expected only to work as the organisational backbone, never to come to the forefront. However, in the case of Upadhyay, an exception had to be made because of the peculiar situation that developed in the party at that juncture. Several years later, Golwalkar would throw some light on the thinking of the RSS leadership at that time. “He (Deen Dayal) really never wanted this high honour, nor did I wish to burden him with it. But circumstances so contrived that I had to ask him to accept the president post. He obeyed like a true swayamsevak, which he was,” said Golwalkar.

But this arrangement was short-lived. Two months after becoming the president, on February 11, 1968, Upadhyay’s body was found by the side of the railway track near Mughal Sarai station in Uttar Pradesh. He was just 52. He was the second top Jana Sangh leader to die under mysterious circumstances — the first being the founder, Syama Prasad Mookerjee, who also died mysteriously on June 23, 1953. Mookerjee too was 52 at the time of his demise.

(The article was originally published in Indian Express on September 25, 2019. The views expressed are personal)