|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

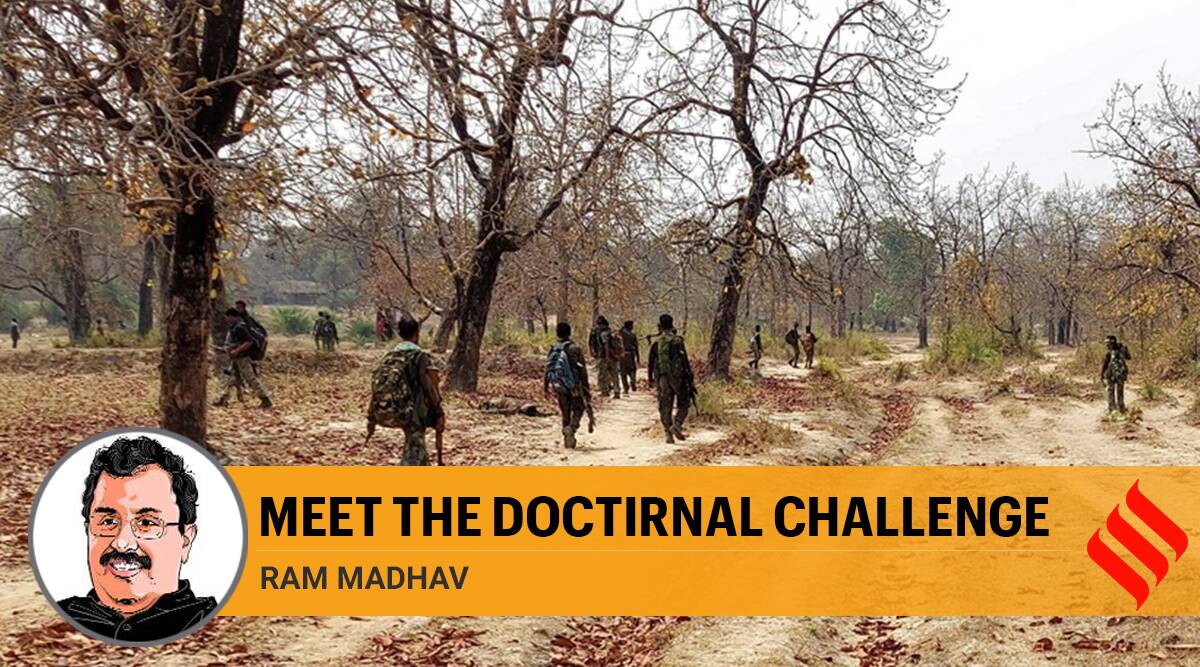

Maoists, like all insurgents, brainwash leaders and cadres. Understanding this doctrinal challenge should be essential any strategy against them

In the last decade, a Union Home Minister offered the olive branch of talks to the Maoists if they shun violence. He also unsuccessfully attempted to deploy the army in Maoist-insurgency areas. Another Home Minister believed that the Maoists were losing the battle and were “on the run”. He advocated aggressive counterinsurgency measures to end the menace. Yet the violence and killings did not end. A third minister is now talking about the government’s resolve to take the fight to its “logical end”. But the challenge is to develop clarity about how this logical end can be reached.

When the Maoists killed 25 senior leaders of the Congress, including V C Shukla, Mahendra Karma and Nand Kumar Patel, in Chhattisgarh’s Darbha Valley in May 2013, it was billed as the worst attack in history. There could not have been a greater provocation for tenacious action from the government. But soon, it was out of memory, until the Maoists struck once again with equal ferocity four years later. This time it was the CRPF — who Maoists derisively call “broiler chicken” — that became the target. In April 2017, the Maoists attacked and killed 25 CRPF personnel in Sukma district. Wreaths were placed, sacrifices mourned, aggressive response promised — and soon, that incident too became history.

Last March, they killed 17 personnel of the Chhattisgarh police in Elmagunda forest in Sukma district. They struck in the same region a few days ago, killing at least 22 jawans of the CAPFs and state police. In the interim, they were indulging in regular incidents, killing several security forces personnel.

Like the previous incidents, the recent one too shall pass unless the government turns its attention to the matter in a more structured and comprehensive way. The thing to understand is that Maoism is not just another form of militancy — it is rooted in political doctrine. Contemporary Maoists are indoctrinated in classical Maoism, presented by Mao Zedong in his 1937 book Lùn Yóuji Zhàn — “On Guerrilla Warfare”. Guerrilla warfare, according to Mao, has not just a military objective but a political one, too: To gradually liberate regions from government control and establish people’s governments in those “liberated zones”.

Whether it is Maoism, Islamic radicalism or terrorism in Kashmir, the three major internal security challenges are all supported by specific doctrines, which are used to brainwash leaders and cadres. This doctrinal challenge requires a doctrinal response. In the absence of such an approach, governments resort to romantic heroism, which may give temporary results but the challenges remain and recur.

The repeated failures of our security forces on the Maoist front do not indicate a lack of government power. They demonstrate the urgent need for a greater understanding of the challenge. The Maoist strategy depends on seven important elements: Arousing and organising people; achieving internal political unity; establishing bases; equipping forces; building national strength; destroying the enemy’s national strength and regaining lost territories. The people, army and territory are the three main ingredients of the Maoist guerrilla warfare strategy. In many cases, these three constitute a nation. Maoists in liberated zones, like the Dandakaranya forests along the borders of Andhra Pradesh, Chhattisgarh, Orissa and Maharashtra, consider themselves independent nations.

Tackling such a challenge requires meticulous planning on all three fronts. People are the biggest weapon for the Maoists. Mao insisted that the revolution should begin from areas that are the most remote from governments. Poor peasants should be indoctrinated and incorporated. The recent visuals of the release of abducted CRPF jawan Rakeshwar Singh Minhas, in which hundreds of locals can be seen, demonstrate the popular support that Maoists enjoy. Singular military operations, whether successful or disastrous, have the potential to push people into the Maoist stranglehold. Therefore, a hybrid approach is needed, involving civic organisations that can reach out and influence the misguided people, together with developmental and counterinsurgency activity by the government.

Demilitarising Maoists should be an objective — this has succeeded in Nepal, Bihar and elsewhere in the past. But it requires deeper engagement with the people in Maoist areas. So far, this engagement was limited to pro-Maoist intellectuals, who are themselves a problem. It is time the government encouraged Gandhians and the RSS to come forward. With its vast experience in tribal activism, the RSS leadership can play an important role in this engagement. It involves risks at one level, but it also engenders confidence in those sections of the Maoists who are looking for a solution.

The repeated failures of security forces in counterinsurgency operations should be blamed on their leadership. The Maoist leadership is well-trained. Leaders should be unyielding in their policies — resolute, loyal, sincere and robust. These men must be well-educated in revolutionary technique, self-confident, able to establish severe discipline, and to cope with counterpropaganda. Guerrilla strategy must be based primarily on “alertness, mobility and attack”, Mao wrote. In recent incidents, leader-less forces were facing the Maoists. It was appalling to see the security forces running helter-skelter, leaving behind their dead. There was no leadership present to regroup the forces for a counterattack and the recovery of personnel and weapons.

Territory is the third issue. Area domination is an accepted counterinsurgency strategy. The Maoist leadership can be targeted not by ill-planned daredevilry but by well-planned area domination. States like Andhra Pradesh have succeeded in decimating Maoism through area domination. Area domination does not mean setting up CAPF camps in Maoist areas. Operations must be followed up with rigorous administrative, developmental and civic activism.

There will be many other tactical challenges, like intelligence gathering, training forces, technology etc. But the central challenge is to develop an internal security doctrine involving administration, development agencies, security forces and civil society organisations.

(The article was originally published in Indian Express on April 13, 2021. Views expressed are personal.)