|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

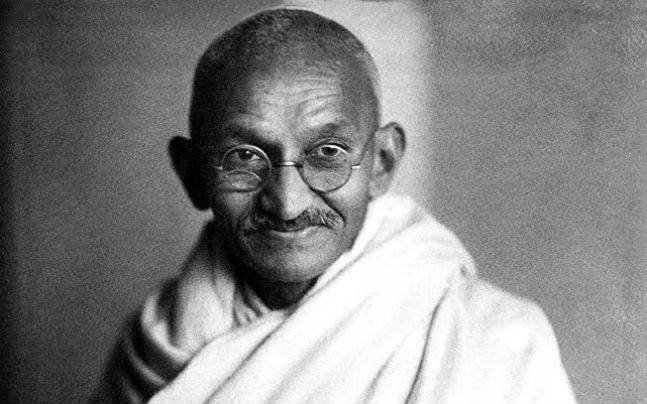

By his actions, Gandhi demonstrated the power of the powerless catapulting him as an icon of thought leadership for all times to come

Mahatma Gandhi is one leader who sparks so much passion and attracts so much attention even after 150 years of his birth and 71 years after demise. There are many who love and admire him; there are many for whom he is the political capital; there are some who hate him. You can love him, pretend to love him or hate him—but you can’t ignore him. “I am not going to keep quiet even after I die”—Gandhiji declared gleefully once long ago. He was right.

Mahatma Gandhi was Asia’s greatest contribution to the world in the last century. His Ahimsa and Satyagraha—Non-violence and Truthful Resistance—were the only original political programmes that any leader had offered in the last century. After Gandhi’s successful experimentation with those programmes in India, they became the essential modus operandi in almost all the struggles for freedom and independence that shook the world in last 70 years and freed people in over 50 countries from the yoke of dictatorships and monarchies. Except for a few countries in Eastern Europe and East Asia that had witnessed violent communist revolutions, all the other countries that have transformed into democracies, had imprints of Gandhian ideals of non-violence and peace in their transformation.

Gandhi had inspired countless leaders, not only in India, but all over the world. What is common among Dominique Pire, a Belgian priest; Adolfo Pérez Esquivel, a teacher in Argentina; Martin Luther King, a civil rights activist in the US; and Nelson Mandela, a freedom fighter in South Africa? All four were Nobel Peace Prize winners. And more importantly, all four had claimed that Mahatma Gandhi was the inspiration for them. India has produced a couple of Nobel laureates, but Gandhi had produced more of them through his ideals. Gandhi continues to inspire countless social activists to this day. There are many Gandhians working silently below the radar in remote far-flung areas among the tribals, scheduled castes and other underprivileged sections of the society.

Today, there are many who swear by Gandhi; but many who hate him too. Churchill hated Gandhi and called him a “half-naked fakir” and bristled at the very idea of him climbing up the steps of the Buckingham Palace to sit face-to-face with the British monarch. But there Gandhi was, in his same loin cloth, nonchalant about criticism from the highest quarters. When someone asked him if his dress was appropriate for the occasion, Gandhi’s reply was that “the King had enough clothes for both of us”.

One quality that distinguished Gandhi from others was his fearlessness. He never bothered about political correctness, etcetera. This quality was a product of his absolute commitment to truth. “The essence of his teaching was fearlessness and truth. The voice was something different from others. It was quiet and low, and yet it could be heard above the shouting of the multitude. Behind the language of peace and friendship, there was power and a determination not to submit to the wrong,” said Nehru once.

Gandhians of today can be angry, harsh and unreasonably critical. But Gandhi was not. In his lifetime, he had endured great criticisms and ridicule. Yet, he never tried to give them back. He used to take criticism and ridicule in his stride and move on. ‘If I had no sense of humour, I would long ago have committed suicide,’ he wrote in 1928 adding, ‘Nobody can hurt me without my permission.’

Gandhi was betrayed by many. Godse was one of them. Gandhi had a premonition about the impending death. He talked about it dozens of times in January 1948; but steadfastly refused to take security. For him, accepting security meant deviating from his commitment to non-violence. “People called me Bapu—a father. If my children want to kill me, so be it,” he would argue. Godse stood in front of him with folded hands, called him “Bapu” and said “namaste”; but the next moment, Gandhi’s two ‘walking sticks’, Manu and Abha, were to the ground. Godse pumped bullets into Gandhi’s chest.

Gandhi was betrayed by Godse and his men; but Gandhism was betrayed by Gandhi’s own followers. Gandhi is for many a political expediency, and Gandhism just a facade. Gandhism doesn’t lie in mechanically rotating the spinning wheel or wearing khadi for public display. “If Gandhism means simply mechanically turning the spinning wheel, it deserves to be destroyed,” Gandhi had himself declared. Gandhism is about truth, transparency, non-violence, openness to criticism, fearlessness, rejection of political correctness and image consciousness.

Gandhi was accused of harshness towards his wife Kastur Ba and other members in the family. Historians tell stories about his harsh treatment of them occasionally. But that was partly also because Gandhi didn’t just preach ideals but wanted to live up to them. Unlike today’s leaders who want others to sacrifice for them while their children and siblings enjoy the fruits of those sacrifices of the others, Gandhi wanted reform to begin at home. When he decided to fight against manual scavenging, he wanted it to start from his family. He asked Kastur Ba to clean up the toilets. Coming from a traditional and orthodox family, Ba didn’t immediately internalise it. Gandhi was angry. But Ba told him that she needed time to understand and follow his philosophy. And she did. There she was, in subsequent struggles of Gandhi, always by his side. She would campaign on his behalf alone on occasions when Gandhi was not available due to incarcerations or ill-health. She went even to Kerala alone to campaign for Harijan Sevak Sangh.

Gandhi’s life was dedicated to the uplift of the downtrodden. He started Harijan Sevak Sangh and fought against caste discrimination and untouchability. After returning from London acquiring a barrister degree, unlike his bete noir Jinnah, Gandhi decided not to start legal practise. He instead chose to live among the poorest of the poor people. Jamnalal Bajaj had donated a piece of land in remote forests near Wardha in Vidarbha. Without hesitation, Gandhi moved into that land. There were no roads, no facilities. Villagers were starkly poor. One night, Kastur Ba fell ill. Gandhi had to move her on a bullock cart and walk for hours in the dark rainy night to reach the nearest hospital in Wardha. Once Ba was cured, Gandhi was back at the village.

Gandhi and Vivekananda had never met. But after a visit to the Belur Mutt, Gandhi confessed that his patriotism had grown manifold after reading about Vivekananda. Vivekananda had, in an electrifying speech, talked about the three qualities needed for all the social reformers. First was an intense feeling. “Do you feel? Do you feel that millions are starving today and millions have been starving for ages? Do you feel that ignorance has come upon this nation as a dark cloud? Does it make you restless? Does it make you sleepless? Has it entered your blood, coursing through your veins, become almost consonant with your heartbeat? Have you almost become mad with that one idea of the misery of your own people and forgotten about your name, fame and prosperity?” he piercingly asked the countrymen. But intense feeling is not everything. Once you have that feeling, look for a way to alleviate the sufferings of the people. The story doesn’t end there also. The most difficult part, according to Vivekananda, was to plunge into the path you have chosen and work. Then and then alone, can you be a real reformer.

Gandhi had fully internalised and lived Vivekananda’s message for the reformers. On the day when the nation was celebrating independence, Gandhi was not in Delhi. He was away at Noakhali in Bengal, among the victims of the worst communal riot that had taken place.

Barack Obama, while visiting a school in 2015, was asked by a student as to what had inspired him that led to his becoming the first-ever Black president of America. Obama said that it was Gandhi. “He gave voice to the voiceless; gave them confidence to rise,” said Obama, repeating Czech scholar Václav Havel’s famous statement about the “power of the powerless”.

There were many in the last century who had worked for the amelioration of the sufferings of the downtrodden. Dr Bhimrao Ambedkar was one among them. Ambedkar had given India a Constitution that was like a beacon of hope to those sections. Ambedkar saw the problems of the downtrodden as social and economic. Hindus and Christians saw those as religious. But Gandhi saw them as moral. Not coercion, nor conversion; but moral reformation should be the way, he believed. Through Harijan Sewak Sangh, he not only wanted the scheduled caste brethren to gain self-confidence but also majorly worked for reform in the thinking of the other sections of the society.

When the Indian Constitution was promulgated, Ambedkar had said that the ideals that inspired the French Revolution—liberty, equality and fraternity—had also found their reflection in it. Liberty and equality could be achieved through constitutional means. Our Constitution provides for the two ideals and also the laws to punish violators. But the third ideal, fraternity, cannot be achieved through mere constitutional mechanisms. It requires public education. For example, untouchability and caste discrimination have been declared as crimes in the Constitution; they are banished from public life. But have they gone from our hearts and minds?

In Gandhi’s and Ambedkar’s time, the struggle was for according equal status to the downtrodden. Programmes like temple entry and common dining were the order of the day. But today the aspirations have changed. The discourse today is no longer about those things anymore. It is about a role in decision-making and an urge for dignity, not charity. Do the downtrodden really have a role in deciding about their own destiny and the destiny of the nation? Or, they are up there just for public display? Despite reservations and affirmative action, how many of them are there today in the bureaucracy, judiciary and academics in decision-making positions? It should be the logical next step in Gandhian reform.

So much filth has been written about Gandhi and women. Gandhi lived a transparent life. He would never sleep with the doors and windows of his bedroom shut. How many of us do that? He had enormous respect for women. He declared that he would consider that day as the real day of independence when a woman in this country would roam about freely on the streets alone at midnight. Many would interpret it as a suggestion for the security of women. It is, but it is more than that.

It is about the way we look at and treat our women. Do we see it as an equal right of a woman, just like that of a man, to be seen on the streets at midnight? Or we perceive those women as promiscuous and with loose morals? Perhaps Gandhi was indicating about the need for a perceptional reform. We talk so much about security of women. It is important. We have laws for the same. Nirbhaya law is the latest and most stringent. Yet, have the atrocities on women stopped? Can laws ensure full safety and security for women? What is of equal importance together with laws is to change the perception of the society about women.

To talk about empowerment, etcetera, is patronising today. Same are clichés like ‘worship of women’, etcetera. What women want today is dignity and respect. That was the reply given by Vivekananda when someone asked him about women’s security. Laughing out loudly at the question, Vivekananda reminds the questioner, that women are Shakti, Durga and Bhagwati. No one needs to protect them, they can do that themselves. But everyone needs to respect them. Respect and dignity, with no riders like how they dress or how they look, is what the society needs to be taught about its outlook towards women.

“Gandhi can be killed, but not Gandhism,” declared Gandhi. Gandhism for the 21st century lies in the principles like dignity, equal participation in decision-making and respect.

Gandhi’s life was a pilgrimage. He had gone on experimenting with his life, learning through those experiences and in the end, left behind a rich repository of wisdom for generations to come.

Chalte Chalte Raah Ban Gaye;

Jalte Jalte Daah Ban Gaye;

Bhakt Swayam Bhagwan Ban Gaye

(By treading the chosen path, he became the path himself; by burning in the fire, he became the flames himself; by prayer and meditation, the devotee himself became the deity)

This famous poem of Atal Bihari Vajpayee aptly applies to Gandhi. Atalji had ended the poem by saying:

Aaj nahi Vah, kintu path par

Charan chinh ankit hai,

Manu ke vamsaj pralay kaal se

Kyun shankit hai

Yadi Ramakrishna gaye, to Vivekananda sesh hai

(He is no more today, but the footsteps remain; Why should the descendants of Manu be apprehensive of the impending disasters?; Ramakrishna has gone, but Vivekanandas are still there)

Gandhi is no more; but there are Gandhians who can inspire us and lead us in creating more Gandhians through the true ideals of Gandhism.

(Reproduced from the text of an address at the Mount Carmel College, Bengaluru on 26th November, 2019 and was originally published in OPEN Magazine on November 30, 2019)