|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

It is an ambitious vision. But the path to it should be pragmatic. In today’s context the path should mean leaner government, ease of doing business, greater investments, massive employment generation and greater integration with the global economy, not just as a beneficiary, but as a contributor.

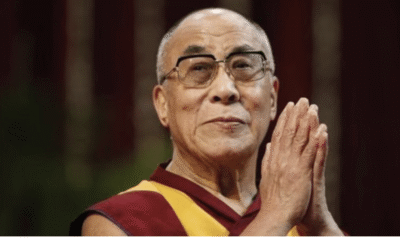

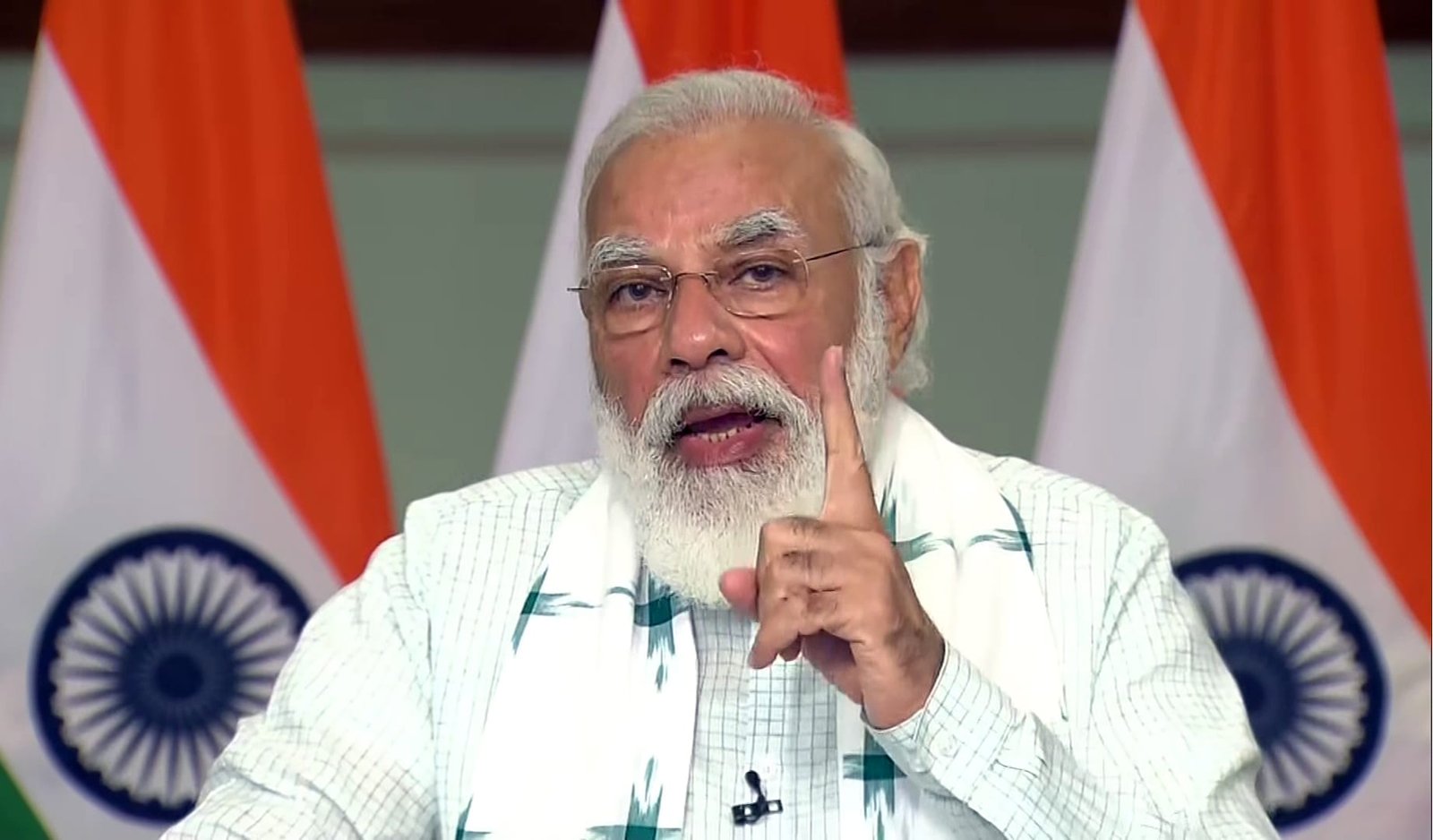

When Prime Minister Narendra Modi spoke about Atmanirbhar Bharat in this year’s Independence Day address, he was not making any retrograde economic statement, nor was he reverting India into the old protectionist mode. The economic model that he pursued in the last six years has been a very contemporary version of the human-centric economic liberalism with self-reliance at its core. He first invoked the Atmanirbhar concept in an address to the nation during the Covid lockdown on 12 May this year. In that speech he gave the slogan “Vocal for Local”. Later, in his Independence Day address, he spoke about “Make for World”. In the last six years, the Modi government has also been aggressively pursuing “Make in India”. Modi’s Atmanirbhar revolves round these three slogans—Vocal for Local, Make in India and Make for World.

Some insist that Atmanirbhar—self-reliance—is not a new concept. It is true that Prime Ministers Jawaharlal Nehru to Indira Gandhi to P.V. Narasimha Rao, had all spoken about it in the past. However, each one of them had left India less self-reliant and more dependent on other countries.

Economic self-reliance was interpreted by each one of these leaders differently. Jawaharlal Nehru chose socialism and government control as the path to self-reliance. Building big dams and huge public sector enterprises—“temples of modern India”—became the main goal of his self-reliance model. But his obsession with “Socialistic pattern of society” had led to shrunk job opportunities and the flight of talent in the 1950s and 1960s. For Indira Gandhi, self-reliance remained a mere slogan. Chandrashekhar as Prime Minister had to mortgage the country’s gold to the Bank of England in 1991 to avoid the humiliation of becoming a defaulter. By the time Narasimha Rao became the Prime Minister in 1991, the country’s economy was in tatters. For Narasimha Rao’s government, self-reliance thus meant the ability to service debts on schedule. In his famous address to the AICC in 1992, Rao summed up his vision for self-reliance as “we should be indebted only to the extent we have capacity to repay”. Rao couldn’t fully unshackle the country from the Nehruvian mixed economy. Yet, with Dr Manmohan Singh’ support, he opened it up for global integration.

Atmanirbhar for Prime Minister Atal Bihari Vajpayee involved “Atma-Shakti”—unleashing inner potential. The Vajpayee era witnessed the dismantling of the burdensome structures of the command economy through initiatives like disinvestment. Infrastructure projects like the Golden Quadrilateral and rural roads scheme have pushed the demand up and accelerated the economy, which resulted in a solid GDP growth rate of 8.5% by 2003-04.

The global recession of 2008-9, followed by the disastrous economic policies and endemic corruption of the UPA government, have left the economy in dire straits when Modi took over in 2014. Modi envisioned a self-reliance model based on the new economic reality of the country and the world. In his Independence Day address he stressed that India “does not advocate self-centric arrangements when it comes to self-reliance. India’s self-reliance is ingrained in the happiness, cooperation and peace of the world.”

Countries like Japan, China and Israel, which started their national reconstruction around the same time as that of Independent India, have all adopted Atmanirbhar as the foundation for their future growth. Each country had its own path to self-reliance. Sakuma Shozan is considered the father of Japan’s modernisation. His famous slogan in the 19th century, which Japan vigorously adopted after 1950, was: “Japanese morals and Western technology”. Japan depended heavily on western technology, without allowing western culture to influence it. In a few decades’ time it became self-reliant in technology too.

China under Deng Xiaoping initiated economic revival in the early 1980s, with a single-minded focus on growth. A new concept of “GDP-ism” was coined to suggest that the objective of the Communist agenda should be to toil for higher GDP growth. From 1982 onwards, for almost three decades, China maintained an annual GDP growth of above 8%. GDP-ism became the mantra for the government as well as the people. China and India were at the same economic threshold in 1980, but in the following three decades, China surged ahead.

The start-up industry is a major player in the story of Israel’s economic success. It is a “Can-Do” nation. Israelis will never be content with what they have; they always try to innovate and improve. When Israel joined the world’s club of the rich—OECD group in 2009, it had a GDP higher than the group’s average.

These nations offer a fresh perspective. Atmanirbhar is an ambitious vision. But the path to it should be pragmatic. In today’s context the path should mean leaner government, ease of doing business, greater investments, massive employment generation and greater integration with the global economy, not just as a beneficiary, but as a contributor. India needs to focus on each one of these to achieve real Atmanirbharta. “Minimum Government-Maximum Governance” has been the Modi government’s motto from the beginning. Similarly, on the “ease of doing business” index, India under Modi improved its ratings substantially. The government is committed to doing more in the direction. The inflow of FDI has been impressive. But India has to now look for investment linked to employment generation more. India should target 150 million jobs in the next five years. While MSMEs are main providers of jobs, the focus on medium and large industries in sectors like manufacturing is also important because they will provide medium and high end jobs in abundance.

Atmanirbharta follows in three stages—Atma Gaurav (self-dignity), Atma Samriddhi (self-sufficiency) and Atma Vishwas (self-confidence). Modi’s call of “Vocal for Local” is about self-dignity or Swadeshi. His “Make in India” is about self-sufficiency—building domestic capability for domestic needs. But the third call of “Make for World” is also equally important. It is about our self-confidence. From a raw material supplier, India’s economy has to mature into a brand creator in the world. In a fascinating book, Too Small To Fail (TSTF), R. James Breiding narrates how not just the big economies like America and China, but even the smaller ones like Finland, Singapore, Norway and Sweden have risen to play a significant role in the world economy through their global brands. India can learn many lessons from their experience too.

Because India as a big country cannot aim for anything less.

(The article was originally published in The Sunday Guardian on September 6, 2020. Views expressed are personal.)