|

Getting your Trinity Audio player ready...

|

(The article was originally published in Hindustan Times on November 3, 2022. Views expressed are personal.)

History serves the masters of the past. But historians serve the masters of the present too. That’s why Napoleon quipped that history is, after all, a “fable, mutually agreed upon”.

Recently, the accession of the princely state of Jammu & Kashmir U&K) into the Indian Union in October 1947 became a subiect of fabled scrutiny. It may be useful to look at it from the prism of some authentic sources.

There are a few accurate firsthand accounts of the last years of India’s freedom movement in books such as The Transfer of Power in India by VP Menon, The Great Divide by HV Hudson and Mission with Mountbatten by Alan Campbell Johnson. Menon, as secretary to home minister Vallabhbhai Patel, was a party to the events of that period, and Johnson served as Mountbatten’s press attaché. Their accounts tell us that none of the Indian leaders were prepared to leave J&K to Pakistan. The state had “the greatest strategic value, perhaps, in all India”, Mahatma Gandhi emphasised.

That the Indian leaders were keen on not letting Kashmir go to Pakistan became clear when they managed to divide Gurdaspur district and secure two-thirds of it to East Punjab. Gurdaspur was the critical land link to Kashmir. It had a marginal Muslim majority of 51.2%. Mohammad Ali Jinnah was confident that the district would become a part of Pakistan, and consequently, the Maharaja of Kashmir would be left with no choice but to join him. But Jawaharlal Nehru and Patel determinedly prevailed upon the British to avert that eventuality.

That paved the way for the accession of Kashmir to India, about which several myths exist. Patel, ably assisted by Menon, was able to persuade most of the princely states to join the Indian Dominion. However, it was not just Kashmir, Junagadh and Hyderabad, which remained troublesome, but at least another 15 princes, the most prominent among them being the ruler of Jodhpur. It was the Mountbatten-Menon duo that played hardball, with the viceroy warning the Maharaja of Jodhpur that his decision to join Pakistan would “surely be in conflict with the principle underlying the partition of India”, and lead to “serious communal trouble inside the state”. The Maharaja finally signed the accession papers on August 11, not before pulling out his revolver to threaten to kill Menon.

The Maharaja of Kashmir continued to dither. His strained relations with Nehru were a big impediment. In fact, in 1946, he got Nehru arrested when the latter visited Srinagar to support Sheikh Abdullah’s movement. This personal rivalry, together with the urge to remain independent, must have prompted the Maharaja to procrastinate on the question of accession.

Efforts to convince the Maharaja began in May 1947 with JB Kriplani visiting Srinagar. Patel also deployed rulers from Patiala, Kapurthala, Faridkot and some hill states to persuade him. But all those efforts failed.

Mountbatten himself went to Kashmir on June 17-23. Before going, he sought a note from Nehru. In a long note, Nehru made a strong pitch for Kashmir’s accession to India. He also asked Mountbatten to press for the removal of Ramachandra Kak as prime minister (PM) and the release of Sheikh Abdullah. “The normal and obvious course appears to be for Kashmir to join the Constituent Assembly of India”, Nehru insisted in that note. Mountbatten’s mission too failed.

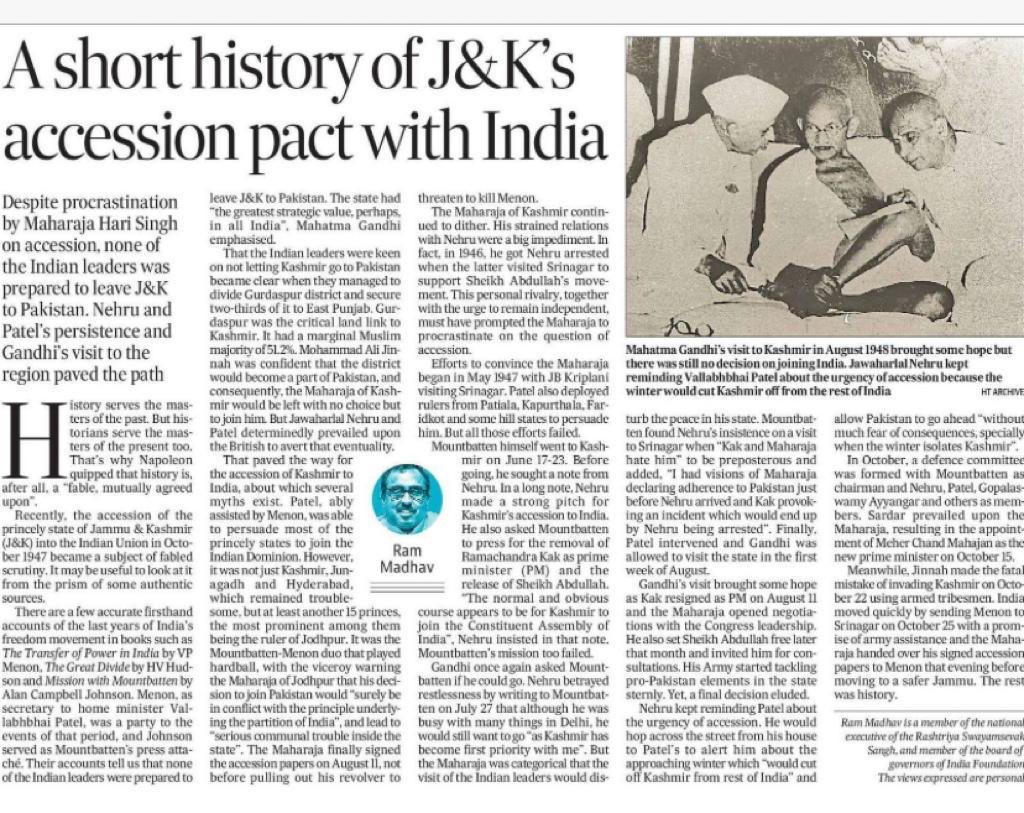

Gandhi once again asked Mountbatten if he could go. Nehru betrayed restlessness by writing to Mountbatten on July 27 that although he was busy with many things in Delhi, he would still want to go “as Kashmir has become first priority with me”. But the Maharaja was categorical that the visit of the Indian leaders would disturb the peace in his state. Mountbatten found Nehru’s insistence on a visit to Srinagar when “Kak and Maharaja hate him” to be preposterous and added, “I had visions of Maharaja declaring adherence to Pakistan just before Nehru arrived and Kak provoking an incident which would end up by Nehru being arrested”. Finally, Patel intervened and Gandhi was allowed to visit the state in the first week of August.

Gandhi’s visit brought some hope as Kak resigned as PM on August 11 and the Maharaja opened negotiations with the Congress leadership. He also set Sheikh Abdullah free later that month and invited him for consultations. His Army started tackling pro-Pakistan elements in the state sternly. Yet, a final decision eluded.

Nehru kept reminding Patel about the urgency of accession. He would hop across the street from his house to Patel’s to alert him about the approaching winter which “would cut off Kashmir from rest of India” and allow Pakistan to go ahead “without much fear of consequences, specially when the winter isolates Kashmir”.

In October, a defence committee was formed with Mountbatten as chairman and Nehru, Patel, Gopalaswamy Ayyangar and others as members. Sardar prevailed upon the Maharaja, resulting in the appointment of Meher Chand Mahajan as the new prime minister on October 15.

Meanwhile, Jinnah made the fatal mistake of invading Kashmir on October 22 using armed tribesmen. India moved quickly by sending Menon to Srinagar on October 25 with a promise of army assistance and the Maharaja handed over his signed accession papers to Menon that evening before moving to a safer Jammu. The rest was history.